The importance of the cane and the terroir in the production of rum

AGRICULTURAL RUM AND THE TERROIR

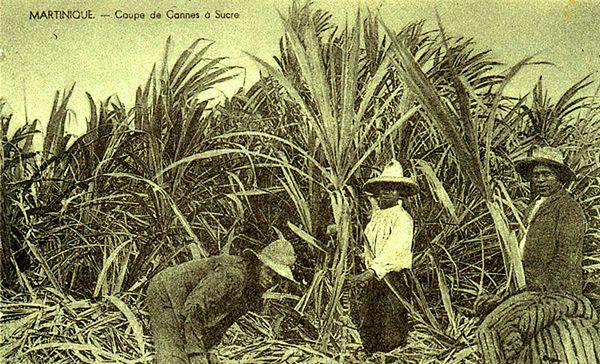

Since the origins of rum as we know it today, which date back to the turn of the 18th century, rum was produced solely from molasses, a by-product of sugar production. It is in Martinique and Guadeloupe that we began to produce rum from the pure juice of the sugar cane, from the second half of the XIXth century.

At the beginning of the same century, competition from sugar beet from the old continent and the blockades caused by the colonial wars left enormous surpluses of cane for the planters, who were extremely numerous on these islands. This led to a reorientation of the sugar cane in favour of the rum and a concentration of the means of production in large central factories, which leads to the isolation of the planters who are a little too far away from it. The latter then began to distil the juice of their cane directly, thus giving birth to the “z’habitant” rum that would later be called “z’habitant”. agricultural rum ».

With regard to molasses rumsthe varieties of cane used and the terroir It is of little importance what kind of sugar they are made from. In fact, to produce sugar, the cane juice is cooked and annealed, which removes all its specificities when the by-product is harvested. There are several grades of molasses, but their classification is based on the amount of fermentable sugars they contain. It is more the methods of fermentation, distillation and ageing that will differentiate these so-called industrial or sugar mill rums.

In the case of agricultural rums, in addition to the production methods, the raw material is of primary importance, since we work with very fresh pure cane juice, which gives rise to a genuine sugar cane brandy.

SUGAR CANE VARIETIES

Here are some examples of sugar cane varieties used by agricultural rum producers. Many of these canes were developed in Barbados, and some in Reunion. Some are more recent than others, for example R.583 was first officially planted in 2008. They are all members of the Saccharum Officinarum family and are the result ofhybridisation (often with Saccharum Robustum) which has enabled each to adapt to a certain type of terrain or climate.

You will also find examples of single-varietal rums corresponding to each type of cane.

Cane zicak B.80.08 Neisson L’Esprit Bio 70

Blue Cane B.69-566 Clement Blue Cane 2020

Non-hybrid Clairin Sajous crystal cane

B.46-364 Bologna Black Cane

Green Cane B.76-56 Montebello Winch

Red cane R.579 Longueteau RSMA Red cane 60°.

A primitive species that was once forgotten has been reintroduced on Rangiroa atoll in French Polynesia, the O’tahiti. It is at the origin of Mana’o and Manutea rums and constitutes a species in its own right which is also part of the lineage of the queen Saccharum Officinarum.

THE NOTION OF TERROIR

The notion of terroir is gaining ground among producers and wine lovers, and with it the interest for transparency and understanding of the product. This is how monovarietal cuvées (like single-varietal wines) came into being in the early 2000s, with Clément spearheading them. Of course, some vintages were already monovarietal (like Neisson 52.5 for example) but distilleries did not necessarily want to mention it until then.

What was initially perceived as a marketing argument alone has finally had an interesting impact. It was a sign of a growing demand for transparency and understanding of this notion of terroir. By understanding that the variety of cane (and above all its terroir) was important in the character of the rumThe spirits enthusiast also realised that the harvest years and their climatic conditions also had a great impact.

HSE also decided to highlight its white rums by indicating the year of their harvest. Then it was Longueteau in Guadeloupe that made a big splash 10 years later by presenting not only monovarietal selections, but also mono-parcel selections, which are undoubtedly even more relevant. The notion of terroir is thus perfectly understandable when one compares a red cane from the seaside to another that has grown in a drier place.

Because it turns out that in the end the variety of cane used counts much less than the sunshine, the orientation, the rainfall or the soil of the plot. This is what the notion of terroir in agricultural rum means. These are the criteria that will determine its sugar content, as well as the freshness of the cut or the way it is crushed.

THE ULTIMATE RESPECT FOR THE TERROIR: ORGANIC

Organic is now the next step towards a full respect of the raw material and the terroir. Neisson has successfully embarked on this adventure, followed by A1710 and Mana’o in Tahiti. Organic sugarcane plots are multiplying in Martinique, and sustainable agriculture (even if it is not necessarily certified as organic) is being emulated throughout the world.

The producers of organic agricultural rums follow the extremely strict specifications of the AB label. First of all, the plot of land must be free of all dangerous pollutants, which must be anticipated a long time in advance because it requires a period of land conversion. During this conversion of the plots and of course afterwards, no phytosanitary products other than organic ones are used and manual or mechanical weeding is used, among many other things, which entails very high costs.

As a reward for all these efforts, we obtain rums that have not been disturbed in any way by external inputs. They are the most faithful expressions of the terroir possible, but without pushing the analogy with wine too far, as rum is a distilled product that leaves a whole lot of elements at the bottom of the still.

It is also worth noting that Neisson cultivates its own yeasts from its organic plots. This is a further step towards a full transcription of their terroir.